Por Cesar Perez Carballada

When companies start, they typically have a simple product line concentrated in a certain price range. If successful, they generally expand the product range to other price tiers and, to do so, they typically use the same brand.

This vertical extension (also called “line extension”) can be in any direction: either a company enters first the higher price tiers and then extends the brand downwards to generate volume or it first enters the lower price tiers and then it expands the brand upwards to improve the margin.

In the former case (moving downwards), the brand is initially positioned as premium, achieving recognition and high margins and, then, its brand equity is used to launch cheaper products, leveraging the “halo effect”: by promoting the expensive product, the company sells many of the cheap products that bear the same brand name. This strategy may be successful as long as the brand doesn’t stretch too much (e.g. covering products that are too cheap) and as long as there are no focused competitors (e.g. other brands that focus on a single price tier and have a more specific and stronger positioning).

In the latter case (moving upwards), the brand is launched in the lower tiers and once it achieves critical mass and distribution, it attacks the premium segments where the margins are more attractive. This strategy is more difficult because it is extremely hard to change consumers’ perception (once they perceive a brand as “cheap”, it’s almost impossible to make them perceive it as “premium”) but it might succeed as long as the initial brand hasn’t started from a too low position and as long as the upward movement aims not at the highest price tiers but just at a higher -still affordable- price.

As result of any of these movements, the company ends up with a stretched brand that covers many price tiers. In this case, how can we determine what the final status of the brand is? In other words, if now the brand is present across price tiers, is it a premium, mid-tier or a low-tier brand?

TOUCHPOINTS

In order to answer the prior question, we need to understand that what matters are not the company’s intentions but how consumers perceive the brand. Branding is a battle of perceptions. Thus, we should consider what elements affect the consumers’ perception?

The answer: every touchpoint.

A touchpoint is any time a person comes in contact with your brand –before, during, or after she purchases something from you. It doesn’t include only your advertising or your sales presentations. It also includes what consumers hear from their friends and family or what they read in social media. It also includes their interactions with your call center or customer service reps. What consumers feel when they visit your store, what they read in a press article, what they see in a review site. In sum, every time a consumer experiences anything related to you brand, her perception is shaped by the interaction.

Whether the brand is perceived as “cheap” or “premium” depends on how the company implements all its touchpoints. Again, it’s not only what we communicate in the ads: when a customer calls our call center, do we make her wait and then a low-wage temporary worker is incentivized to shorten de call or do we answer immediately and solve her problems supporting her with an experienced account representative? In the former case, consumers will perceive our brand as cheap, no matter what we claim in our ads.

In sum, if all the touchpoints in the aggregate convey premiumnes, then the brand will be perceived as such; if the touchpoints account for a “cheap” experience, then the brand will be perceived as such, no matter what our powerpoint says.

Having said that, one of the most important touchpoints is the product itself. Once a consumer purchases our product, its consumption will affect dramatically how the brand is perceived. Even before the purchase, consumers will observe and assess the product, and such interactions will also affect the brand.

Thus, if the brand is stretched to cover too many price tiers, from high-price/high performance to low-price/low performance items, how can we know whether the brand is perceived as low tier or premium?

CENTER OF GRAVITY

In physics, the center of gravity is an imaginary point in a body of matter where the total weight of the body may be thought to be concentrated. The concept is useful in designing static structures (e.g., buildings and bridges) and in predicting the behavior of a moving body when it is acted on by gravity. The location of a body’s center of gravity may coincide with the geometric center of the body, especially in a symmetrically shaped object, but the two may not coincide if the object is asymmetrical or composed of a variety of materials with different masses.

Based on that notion from physics, I have developed a novel concept which can help us to solve the puzzle: the brand’s center of gravity. We can consider the brand as an “object” whose “shape” is determined by all the products that bear the same brand name, thus the brand’s center of gravity would be determined by the quantity and position of the products in the ‘value proposition’ space.

The Value Proposition space has two axes (see next chart): the vertical one refers to the product’s benefits and the horizontal one to its price. Most products will be placed close to the regression line because ‘benefits’ and ‘price’ are in general correlated: the more benefits a product offers, typically the higher its price is. It’s important to note that products above the regression line tend to gain market share while the ones below tend to lose it. There are also clusters of products in zones of similar benefit-price levels, which represent the ‘tiers’: low-tier, mid-tier, high-tier and premium. Just to illustrate the concept, I have added automotive brands in Europe.

Let’s review now specific cases to further develop the concept. If we sell only 2 products under the same brand name (dark blue dots in the next chart, left side), then its “center of gravity” will be the average of both products, in terms of price and benefits (orange dot). If we add 3 new products under the same brand (red dots in the next chart, right side), the new center of gravity will shift correspondingly. The size of the bubbles may represent the number of units sold by each product, signifying the “mass” of each product, and the center of gravity would be the resulting weighted average.

Now, if we sell 20 different products (see next chart) under the same brand, and all of them belong to the premium segment (i.e. high price and high performance), then the brand’s center of gravity will also be located in the premium segment, because it’s situated at the weighted distance of all the products, and we can affirm without doubt that the brand is premium.

We can use the same framework to explore the questions regarding brand extension. For instance, let’s analyze the case of a company that sells 10 products in the mid-tier (see next chart, left side), all of them under the same brand, thus the brand is clearly positioned in the mid-tier (its center of gravity is the orange dot). Let’s say that the company’s executives decide to convert the brand into a premium one in order to charge price premium and, to do so, they decide to launch a new product in the premium segment, is that enough to turn the brand into a premium one? Of course, the executives will tell anyone who wants to listen that now their brand has become a premium one by pointing out to that single SKU, however our intuition tells us something different, and using the concept of ‘center of gravity’ we can prove it quantitatively. As we can see in the next chart (right side), the center of gravity of the brand (the orange dot) barely moved upwards and it still is firmly fixed in the mid-tier, thus, in spite of the existence of the premium product, the brand is still a mid-tier brand. This is an important learning: a single expensive and high performance product does not convert a “cheap” brand into premium if the vast majority of its products still have low price and low performance. It’s amazing how many executives are delusional about this reality and convince themselves that their vast presence in the low tier doesn’t prevent them from having a premium brand and, then, they are puzzled when consumer are not willing to pay a premium price for their products.

Moving on the opposite direction, if a company sells products in the premium segment (see next chart, left side) and, in order to gain volume, it decides to expand the brand downwards by launching cheaper products, the resulting center of gravity will slightly shift downwards but it will still be in the premium segment (next chart, center); however if the company’s executives, tempted by the promise of a higher market share, continue adding cheaper versions (next chart, right side), the brand’s center of gravity will move downwards significantly and the brand will not be premium anymore, which in turn will put at risk the sales of the expensive products because who wants to buy expensive products from a brand that sell mostly low performance and cheap products? This situation is called “brand dilution” and it is one of the most common ways to kill a brand.

Let’s look at a real example from the automotive industry (see next chart).

Each point represents one of the 44 model variants under the brand Volkswagen Golf across many price tiers in Europe from the cheapest VW Golf 1.2 TSI BlueMotion at 16.975 € to the expensive VW Golf R at 38.325 €. As we can see in the chart, a consumer will be exposed to a mix of mid-tier and high-end products, so is the brand Volkswagen Golf a mid or high-tier one?

The location of the brand’s center of gravity is on the upper limit of the mid-tier, at 24,726 € and almost exactly over the correlation line (the orange dot in the prior chart), thus, even when the brand also sells very expensive models, it is an upper mid-tier brand.

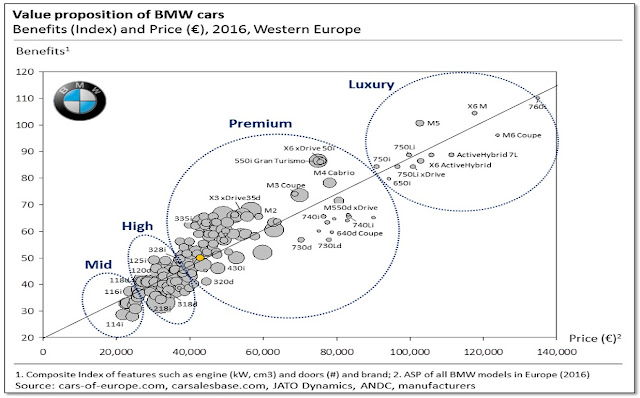

This is another real example, this time for BMW:

BMW also covers many price tiers with 158 models in Europe, from the model 114i (21,900 €) to the 760i (134,900 €). As before, we calculate the brand’s center of gravity (the orange dot) and we see that it’s located at 49,142 €, within the premium segment, due to which we can conclude that BMW is a premium brand in spite of its presence in the high-tier (3 series) and in the luxury segment (6 and 7 series). It’s important to note that BMW’s center of gravity could be higher if it wasn’t for all the cheaper models in the mid-tier and high-tier (1 and 2 Series). Also, we can see that, since the center of gravity is above the correlation line, the brand will tend to gain market share over time.

In order to be more precise, we should weighted the car models in the chart by their sales numbers because if the cheap models sell ten times more than the expensive ones, then consumers are ten times more likely to interact with the brand via the cheap models, and their brand perception will be shaped more strongly by the cheap products. If we add that dimension (size of the bubbles proportional to the units sold by each model), we get the following chart:

As we can see in the prior chart, there is a large concentration of sales in the lower premium and high-tier. Thus, when considering the actual unit sales numbers, BMW’s center of gravity drops to 42,779 €, still in the premium segment but closer to the high-tier limit. Also, the center of gravity moved closer to the regression line, suggesting that the strong presence of cheaper products decreases the chance of gaining market share in the long run due to a lower value proposition. This is a result of the strong presence of the 1 and 2 Series which represent more than 32% of all BMW sales (in units) in Europe. The 1 Series is particularly dangerous for the brand because it means that BMW set foot in the mid-tier. The 1 Series can help BMW to increase its market share in the short term (more than 130,000 units sold in Europe) but it risks brand dilution: the presence of these cheap models drags the premiuness of the brand by bringing its center of gravity down. It’s true that BMW tries to minimize this effect by charging a price premium vs the competitors’ cars with similar performance but premium consumers sooner or later will notice this dilution and next time they are on the market for a premium car they may decide that they want a real premium brand and switch to Porsche. That’s called the 'brand dilution trap': more market share in the short term at the expense of sales of expensive high-margin models in the future. Perhaps that’s why BMW does not sell the 1 Series in the US even when doing so would generate a large volume of sales, and as result of that, in that country the cheaper model starts at $ 34,950, avoiding the presence in the lower segments and increasing the premiumness of the brand.

We need to bear in mind that the other touchpoints (besides the products) such as advertising, distribution channels and word of mouth also influence how the brand is perceived and they can move the “center of gravity” up or down; however, they cannot fully offset the products’ reality: if the majority of our products are in the mid-tier, no matter what we say in our ads, consumers will think that it is a mid-tier brand.

*****

The brand’s center of gravity is a powerful novel concept which allows us to calculate and to visualize where a brand is located, even if it covers many products across price tiers. This framework also helps us to understand the impact of brand extension, including the idea that extending the brand down can be dangerous due to the risk of dilution. Now you can use this concept to determine your brand’s center of gravity and that of your competitors.

___________________________________________________________

- Share here you opinion of this article

- Send this article by email

___________________________________________________________

Sources:

___________________________________________________________

Author: César Pérez Carballada

Article published inhttp://www.marketisimo.com/ Continuar leyendo el resto del artículo...